How a group chat protects Linda Vista neighbors from ICE

Residents in a group chat keep track of when immigration officials are present and whether it's safe for people to leave their homes.

Written by Kate Morrissey, Edited by Lauren J. Mapp

Maria never intended to become a community leader.

She and her husband often worked multiple jobs to take care of their children after they moved to the United States from Oaxaca, Mexico.

But after she saw the power of organizing when her daughter was detained by immigration officials more than a decade ago, she found herself playing a central role in connecting her neighbors with human rights resources.

Now, Maria has rallied her community in a group chat that allows neighbors to update each other on immigration enforcement activity in Linda Vista. The network could serve as a model for other communities wanting to do more to protect their neighbors from the Trump administration's ramped up immigration enforcement.

“In the moment we aren't prepared, they can take us,” Maria said in Spanish. “For me, the mutual support, honesty and respect in the community counts a lot. That's what has maintained us.”

Maria and other community members in this article are not being fully identified due to concerns about retaliation.

Community patrols have checked certain San Diego neighborhoods for immigration enforcement activity for years. Unión del Barrio organizes volunteers to drive up and down the streets of several San Diego neighborhoods, including Linda Vista, on a rotating basis looking for signs of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

But the group chat came about after President Donald Trump's reelection and fears about mass deportations grew in Linda Vista's immigrant community. Maria recalled attending a meeting where organizations promised to fight for immigrants. She left thinking the only way that the community could stay safe was to communicate closely.

“She was the voice, the root of everything,” Maria's husband said. “And it grew and grew.”

He emphasized that the group chat wouldn't have been possible without the years of work that Maria put into knowing and serving her community.

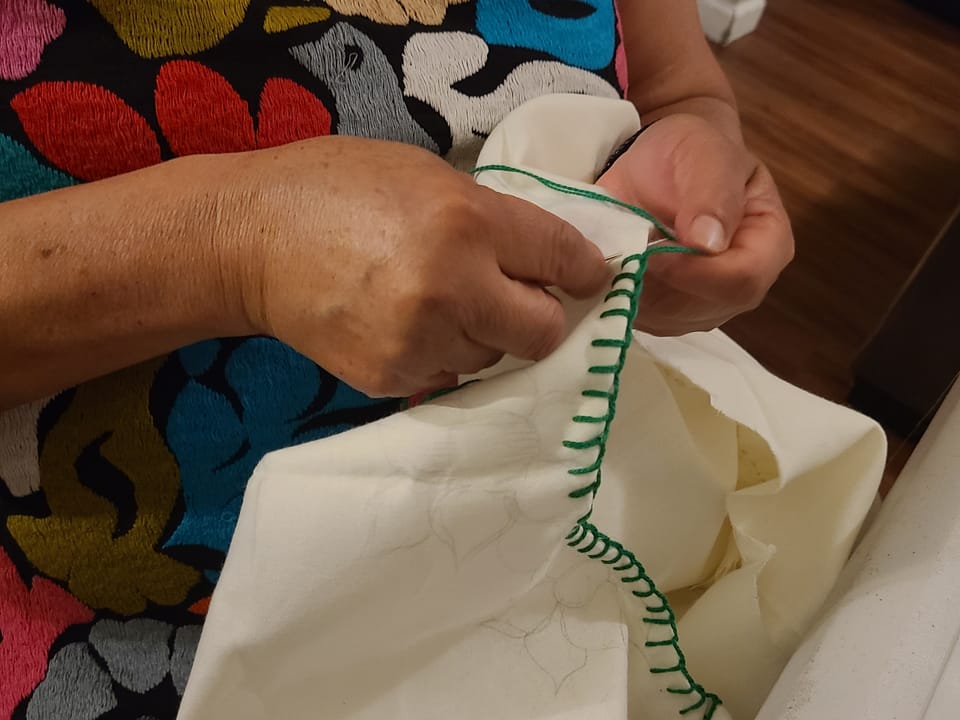

When the deportation scare happened with their daughter, he and Maria found support from community organizations such as the American Friends Service Committee. After their daughter returned home, they attended human rights workshops with the organization and began promoting educational resources in their community.

Though her husband stepped down from a leadership role to focus more on their family after a few years, Maria continued showing up to meetings and bringing community members together over a variety of issues from policing to housing.

She was led by gratitude, Maria said, a practice that she learned from her family back in Oaxaca.

“It's not just me. It's never been just me,” Maria said. “It's the community, the people who have supported me, the organizations who have prepared me. I have never been alone.”

After Trump's reelection, with the help of her more technologically savvy family members, Maria sent invites to the contacts that she gathered over the years, and, a few months ago, the group chat was born.

Residents post when they see something out of the ordinary that might indicate ICE presence.

One Linda Vista resident said he drives the neighborhood most mornings, even when the organization isn't patrolling, and reports to the group chat what he sees. Even sharing that he didn't see anything can help people feel safer to leave their homes to take children to school or buy food, he said.

“The main reason is to be part of the community,” said the man, who has time to do the daily patrols because he is retired.

If someone reports suspicious looking vehicles or potential enforcement activity in the group chat, he often goes to investigate and report back.

Other community members will post in the group chat when they happen to go to the grocery store or other common destinations to say that no immigration officers are there.

Before the group, Maria said, community members told her some of them stayed in their homes for two to three weeks at a time because they were so afraid of ICE. Now they feel more empowered to be out living their lives, she said.

“They said it was a relief to find the group,” Maria said.

The messages aren't just about ICE. Recently, one person asked if anyone knew about a room for rent. Another asked about the times for Mass at a local church.

Maria's husband said he thinks the group needs to recruit more young people, particularly U.S. citizens, to help with the verification work.

In the meantime, Unión del Barrio patrols continue in the neighborhood and bring more awareness to the community's efforts.

As the sun was peeking over the neighborhood's hills on the day of a recent patrol, Benjamin Prado, a volunteer with Unión del Barrio and coordinator for the American Friends Service Committee U.S./Mexico Border Program, stopped to talk to two men standing and chatting next to a landscaping truck.

Prado handed the men a flyer that gave examples of the types of vehicles that immigration officials often drive — gray or black U.S. brands such as Fords, Chevys, Dodges or GMCs.

The men thanked him, and Prado and the retired volunteer drove off, continuing to scan alleys and side streets for clusters of unmarked cars that could belong to ICE.

“Everything is calm today,” Prado said as he and the volunteer finished up their morning route.

“That's how we want it,” the volunteer responded.